Do you know how to handle chemical burns? Do you have a mandatory 20-minute on scene flush policy?

Having had the opportunity to travel nationally, teaching hazardous materials response and prevention for over 25-years, I became aware that there was a common thread between many different firefighters that I spoke to during class breaks. All of them candidly shared that when they were exposed to a hazardous material, both their medics and the hospital were ill prepared to deal with their injuries... but they promised to do better next time.

In an effort to prevent any of you from becoming Guinea Pigs... I share this Standard Operating Guideline that was written years ago by the Santa Clara County EMS Authority.

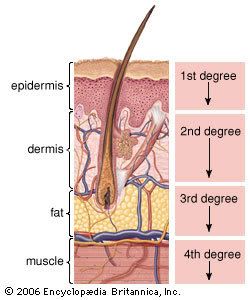

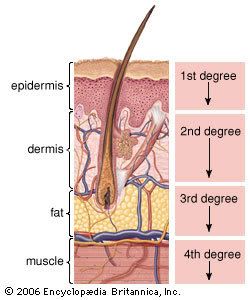

Burn Review:

Here's the example that was shared during the seminar:

Scenario One: A young child hears a knock on the front door and goes to the door to answer it. After opening the door, a familiar figure stands there with a glass jar filled with liquid. The stranger was the step-father taking revenge against his ex-wife on the child. One gallon of hydrochloric acid was splashed directly into the childs face and chest. 911 was called and within minutes an engine company pulled up on scene and evaluated the scene.

Immediately, the Fire Captain grabbed the kid by the back of the neck, took him out to the front yard and followed a new policy taught to the fire department by nurses from the local emergency room. The policy was simple, anyone exposed to a liquid corrosive hazardous material shall be flushed for a minimum of 20-minutes, on scene.

About 10-minutes into the incident, an over zealous private ambulance company medic insisted that he take the patient immediately to the hospital. The Captain did not relent his hold on the kid or the flow of water flushing his eyes and face. The more insistent the medic became, the more the Captain felt any degree of patience. The medic was eventually arrested under protest and placed into the back of a patrol car.

The child was released 10-minutes later by the fire department and was transported to the local hospital. The child was released 2-hours later with no injury, burns or damage to his eyes, all because the fire department followed these standardized rules for chemical exposure.

The solution to pollution is dilution. Anyone exposed to a hazardous materials needs to be evaluated as soon as possible but if they have chemicals on them, you need to ensure that as much of the chemicals have been flushed or vacuumed off prior to transport to a medical facility.

Scenario Two: A worker accidentally falls into a vat of sodium hydroxide (Lye). In the excitement , a helicopter is dispatched to the scene to immediately get this man to the hospital. Emotions were raging and to protect the pilot and crew from exposure, the victim was placed into a body bag to prevent secondary contamination. When they arrived at the hospital, the victim had expired and had suffered fourth degree burns.

Immediate decontamination makes sense using the 20-minute on scene flush policy.

Discuss this concept with your local EMSA (Emergency Medical Services Agency) if you do not have this guideline as one of the tools used to minimize the damage caused from these types of exposures.

Being expedient about providing the flushing is paramount if you are going to make a difference. Couple this with the elderly or small children and the results may prove to be fatal.

Remember that with corrosive burns for example, what is happening is that you are first off getting an exothermic reaction which is the generation of heat that causes the actual chemical burns. Secondly, the chemicals break down intercelluar walls and get transported via your lympatic system to other parts of the body. The sooner the chemical(s) are removed the better chance your patient has of surving this insult and will suffer a lesser degree of burn.

The life you save may be your own...

Stay safe,

Mike Schlags

Santa Barbara, CA

mschlags@yahoo.com

In an effort to prevent any of you from becoming Guinea Pigs... I share this Standard Operating Guideline that was written years ago by the Santa Clara County EMS Authority.

Burn Review:

Here's the example that was shared during the seminar:

Scenario One: A young child hears a knock on the front door and goes to the door to answer it. After opening the door, a familiar figure stands there with a glass jar filled with liquid. The stranger was the step-father taking revenge against his ex-wife on the child. One gallon of hydrochloric acid was splashed directly into the childs face and chest. 911 was called and within minutes an engine company pulled up on scene and evaluated the scene.

Immediately, the Fire Captain grabbed the kid by the back of the neck, took him out to the front yard and followed a new policy taught to the fire department by nurses from the local emergency room. The policy was simple, anyone exposed to a liquid corrosive hazardous material shall be flushed for a minimum of 20-minutes, on scene.

About 10-minutes into the incident, an over zealous private ambulance company medic insisted that he take the patient immediately to the hospital. The Captain did not relent his hold on the kid or the flow of water flushing his eyes and face. The more insistent the medic became, the more the Captain felt any degree of patience. The medic was eventually arrested under protest and placed into the back of a patrol car.

The child was released 10-minutes later by the fire department and was transported to the local hospital. The child was released 2-hours later with no injury, burns or damage to his eyes, all because the fire department followed these standardized rules for chemical exposure.

The solution to pollution is dilution. Anyone exposed to a hazardous materials needs to be evaluated as soon as possible but if they have chemicals on them, you need to ensure that as much of the chemicals have been flushed or vacuumed off prior to transport to a medical facility.

Scenario Two: A worker accidentally falls into a vat of sodium hydroxide (Lye). In the excitement , a helicopter is dispatched to the scene to immediately get this man to the hospital. Emotions were raging and to protect the pilot and crew from exposure, the victim was placed into a body bag to prevent secondary contamination. When they arrived at the hospital, the victim had expired and had suffered fourth degree burns.

Immediate decontamination makes sense using the 20-minute on scene flush policy.

Discuss this concept with your local EMSA (Emergency Medical Services Agency) if you do not have this guideline as one of the tools used to minimize the damage caused from these types of exposures.

Being expedient about providing the flushing is paramount if you are going to make a difference. Couple this with the elderly or small children and the results may prove to be fatal.

Remember that with corrosive burns for example, what is happening is that you are first off getting an exothermic reaction which is the generation of heat that causes the actual chemical burns. Secondly, the chemicals break down intercelluar walls and get transported via your lympatic system to other parts of the body. The sooner the chemical(s) are removed the better chance your patient has of surving this insult and will suffer a lesser degree of burn.

The life you save may be your own...

Stay safe,

Mike Schlags

Santa Barbara, CA

mschlags@yahoo.com

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

-

Permalink Reply by turk182 on September 9, 2008 at 10:11am

-

so it's 20 minutes on all liquid corrosives.

And can a fire department get introuble for not releasing a patient to EMS?

-

Permalink Reply by Ben Waller on September 9, 2008 at 10:48am

-

Turk,

Most states have an "Emergency Powers of Fire Departments Act" or similar law that essentially states that the Fire Chief or his/her designee is in charge of fires and other emergencies as long as that emergency isn't shooting at you. That includes hazmat incidents.

The Fire Chief (or designee) is federally mandated as the Incident Commander of ALL hazardous materials incidents under SARA Title III, 29 CFR 1910.120.

Corrosives are hazardous materials. A patient splashed with hazardous materials is part of the hazmat incident. The fire department is in charge of that patient until they deem that the patient has been sufficiently decontaminated.

"Sufficiently Decontaminated" means that the chemical has been diluted or washed off enough that the chemical won't harm the patient further and that the chemical won't contaminate the EMS personnel, the ambulance, the hospital, or otherwise spread contamination away from the scene.

If the EMS personnel aren't part of the hazmat team and/or aren't trained in the use of chemically-protective clothing and SCBA, then they have no business handling contaminated patients until the patients have been adequately decontaminated. Federal law and most state laws will back you up on this.

Find out what your state laws say, inform your fire and EMS people, and prepare a plan that is both legally defensible and that won't make a bad scene worse.

Ben

-

Permalink Reply by Ben Waller on September 9, 2008 at 11:01am

-

Mike,

I agree completely, and would add that the 20 minutes should be from a deluge/mass decon system. I've run several bad corrosive exposures, and my first actions were to get the patient naked and in the shower in fixed facilities, and in a mass decon stream if it was a transportation incident.

A couple of additions to your excellent post -

Most EMS helicopters will not transport ANY patient who has been injured as the result of a hazmat incident. The potential for contaminating a multi-million-dollar aircraft and taking it permenantly out of service for a single patient are just too great. Additionally, many toxins and corrosives will off-gas harmful fumes that can injure or incapacitate the pilot in flight. Incapacitated helicopter pilot = CRASH.

There are also some water reactive corrosives, although most of them are in solid or gel form. Pteropthalic Acid Anhydride is one such corrosive. (Don't ask how I know about this particular chemical.) If the chemical has "anhydride" in the name, that means that it has chemically had the water removed from it, and that it is now WATER REACTIVE. (Think "Anhydrous Ammonia as a common example) Adding water to water-reactive chemicals is generally a bad thing, or so I've heard.

Another consideration is that the 20 CFR 1910.120 regulations don't require runoff control for emergency patient decon, but you still need to consider where the runoff goes, especially if you're standing in it.

-

Permalink Reply by Jay Nicholson on September 9, 2008 at 11:15am

-

Find out what your state laws say, inform your fire and EMS people, and prepare a plan that is both legally defensible and that won't make a bad scene worse.

Real important statement. In one of my early ICS classes, many yrs ago, I couldn't believe that we, the FD, were not ultimately in charge of every scene. Our storm drains here dump into the bay/ocean untreated. If an incident could possibly spread to these area, the USCG has jurisdiction. Back country gets you the Dept. of Fish and Game. Fortionately, inter-agency communications and cooperation prevents hard-headness disease.

There was a large tire store downtown that burned for hours one morning. The million or so gallons of water that was used to put this out flowed into the bay. The USCG didn't come in and tell the deputy chief to stop polluting the bay with run-off. But the USCG did take an active role during the fire to prevent damage to the bay

-

Permalink Reply by turk182 on September 9, 2008 at 11:18am

-

Thanks Ben,

Sometimes it gets hard to tell were the fire departments patient care ends and ems begins.

-

Permalink Reply by Ben Waller on September 9, 2008 at 11:32am

-

Jay,

Remember that most fire departments derive their legal authority from state or local laws. Federal law can trump the local fire department's powers in some circumstances.

I've been on a large diesel fuel spill (pipeline break) where the Coast Guard showed up and took over. They stated that they had the legal authority to do so. The CG commander then started spitting out orders that violated the local fire department/EMS/hazmat team safety procedures and SOGs. The fire chief and hazmat coordinators tried calm and professional negotiation, and were told flatly that the Coast Guard was in charge and that we were going to do it their way. The fire chief told the Coast Guard that since they had taken over the scene, that they had just relieved the local fire department of the duty to act, that all local resources were going to pack up and leave, and that the Coast Guard would now be legally liable for whatever happened after they took over.

At that point, the fire chief invoked 1910.120 and his power to remain in Command. At that point, the unhappy CG commander backed down, and everyone started working together to mitigate the incident.

The local fire chief clearly had the legal authority to remain in Command under 1910.120. Because the spill involved a navigable waterway, the CG had the legal authority to participate.

The keys are 1) know the law and 2) work with the other response stakeholders (EMS, hazmat team, Coast Guard, Fish and Wildlife, DOT, or whoever) to resolve these issues before an incident occurs. That eliminates the need for the Command Post to be constructed from PortaPotties, since there won't be as many pissing contests.

-

Permalink Reply by Mike Schlags (Captain Busy) Retd on September 9, 2008 at 11:37am

-

So this farmer in the central part of California is working on an anhydrous ammonia line that was connected to a nurse tank on his tractor. These tractors use high pressure lines to distribute the NH3.

One of the pressurized lines broke, releasing the NH3 in a stream of liquid that once it hit the air, expanded many times and besides coating the farmers chest and face, caused inhalation issues... ammonia...

Somehow, the farmer was able to move up wind to get out of the NH3 cloud, do some significant coughing and eventually tightened up the connection that was responsible for the leak. He then simply just went back to work on his field, and didn't return back home until hours later. By the time he got home, everywhere that the NH3 had made contact with his body started to cause major tissue necrosis (death). The only reason that he even called us was because his skin had started to stink so bad that he couldn't handle the smell.

This man was taken to the local hospital and was admitted to the burn ward due to deep tissue burns from the NH3 exposure. What went wrong? What happened here?

What is sad is that all this guy should have done is simply hose himself off, remove the contaminated clothing, wash with soap and water and call it a day. The respiratory insult does have the potential for causing pulmonary edema but for the most part, use of copious amounts of water for someone who has been exposed to NH3 is the treatment of choice and should be done immediately.

NH3 is anhydrous which means that they have taken all the water out. When this stuff gets out of the box it is considered hydroscopic or the chemical has an infinity to pull water out of something. Get it on your skin and the damage can be severe. Amines for example is what you smell when you have rotting flesh. You get this reaction from exposure to the NH3. One thing that people don't consider with NH3 is how cold the chemical is. Injuries from direct chemical contact causes burns associated with very cold materials.

Typically, exposure to NH3 will cause tissue damage to every place on the body that was not covered or protected. Understanding that NH3 requires immediate decontamination should clue you in prevention wise to ensure that water is readily available should something go wrong as described in the above scenario.

Note: "Regulations require that all anhydrous ammonia nurse tanks and applicator tanks carry at least one five-gallon container of clean water. This must be readily available for flushing the eyes and skin in case of exposure. The water should be changed daily to ensure a clean supply. It is also recommended that a second five-gallon container of water be kept on the tractor. This will provide the operator with another source of water for first aid in case the operator is unable to reach t e one on the nurse or applicator tank. Handlers of ammonia should also carry an eight-ounce eye wash plastic water bottle at all times in case an accidental exposure occurs."

Now you know why NH3 rigs carry water and a hose with them. Accidents do happen but the end results can be better controlled if you have the necessary contingency plan in place... So for this particular instance, adding water is a good thing to remember for this type of incident. ms

-

Permalink Reply by Jay Nicholson on September 9, 2008 at 11:42am

-

The keys are 1) know the law and 2) work with the other response stakeholders (EMS, hazmat team, Coast Guard, Fish and Wildlife, DOT, or whoever) to resolve these issues before an incident occurs. That eliminates the need for the Command Post to be constructed from PortaPotties, since there won't be as many pissing contests.

This was the point I was trying to make. But not nearly as eloquently as you. Multi-agency drills are indespensable for creating a sense of co-operation. Sometimes letting the guy in charge think he's in charge is more important than actualy being in charge.

-

Permalink Reply by Damon Dyer on September 9, 2008 at 11:59am

-

Very good forum learned a lot , thank you .

-

Permalink Reply by Ben Waller on September 9, 2008 at 1:33pm

-

Jay,

"Sometimes letting the guy in charge think he's in charge is more important than actualy being in charge."

You need to be careful how you apply that one. If there are unclear lines of authority and one of us gets hurt or killed, then the agency with the statutory authority is going to eat the blame, regardless of who actually screwed up.

Making the key players feel important - certainly. Let them think they're in charge...I'm not sure about that one.

LaValla and Stoeffel (the Washington State guys that crafted a lot of the Mt. St. Helens eruption response) have an emergency planning concept that essentially says that getting all of the stakeholders together and getting them all to buy into the planning process is more important that the details of the resulting plan.

I've found this to be very true.

-

Permalink Reply by Mike Schlags (Captain Busy) Retd on January 27, 2011 at 12:33am

-

EMS can get in trouble for not following on scene life saving precautions, which as outlined, is the 20-minute on scene flush policy for chemical burns. Check and see what your jurisdictions policy is. If there is not a policy, then there is now...

-

Permalink Reply by Norm Tindell on January 27, 2011 at 7:15am

-

And if the material is a dry chemical brush as much off as quickly as possible before irrigating. Example: If it's caustic the water will cause it to burn more, therefore reducing the amount of dry substance on the skin will allow the flushing process to work faster and with less discomfort for the patient.

Specialty Websites

Find Members Fast

Firefighting Videos

© 2026 Created by Firefighter Nation WebChief.

Powered by

![]()

Badges | Contact Firefighter Nation | Privacy Policy | Terms of Service